Threatened by flames, nuclear lab peers into wildfire future

LOS ALAMOS, NM — Public schools were closed, and evacuation bags were packed this week when a persistent wildfire crept within a few miles of Los Alamos, and its associated U.S. National Security Laboratory — where assessing apocalyptic threats is a specialty and wildfires a tempting comparison.

Lighter winds on Friday fueled the most intense airstrike this week on those flames west of Santa Fe and the largest U.S. wildfire burning further east, south of Taos.

“We flew all kinds of aviation today,” Fire Chief Todd Abel said at a Santa Fe National Forest briefing Friday night. “We haven’t had that chance for a long time.”

In Southern California, where a fire has destroyed at least 20 homes south of Los Angeles in the coastal community of Laguna Niguel, Orange County emergency services reduced the mandatory evacuation area from 900 houses to 131 on Friday.

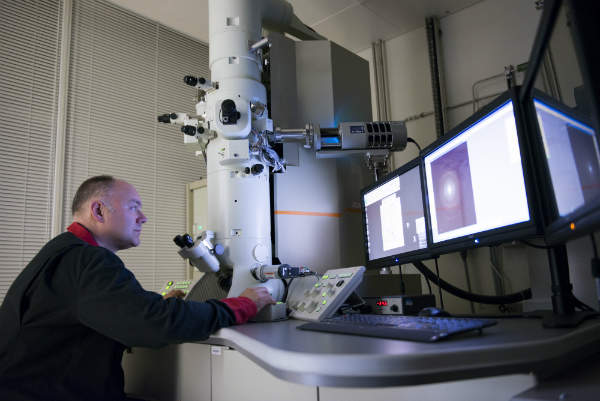

People who remained vigilant to prepare for evacuations west of Santa Fe included scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory tapping supercomputers to look into the future of wildfires in the western U.S., where climate change and an ongoing drought the frequency and intensity of forest and grassland fires.

The research and partnerships could eventually provide reliable predictions that shape how vast tracts of national forests are thinned — or selectively burned — to fend off catastrophic hot fires that could quickly engulf cities, and sterilize soils and ecosystems. It can change forever.

“This is actually something that we’re really trying to leverage to look for ways to deal with fire in the future,” said Rod Linn, a senior lab scientist leading the effort to create a supercomputing tool that will track the outcome. Oterrain and conditions. f fires in specific cases.T

The high stakes in the investigation are prominently displayed during the furious start to the spring wildfire season, including a fire that has steadily spread to Los Alamos National Laboratory, sparking preparations for a potential evacuation.

The lab grew out of World War II efforts to design nuclear weapons at Los Alamos as part of the Manhattan Project. It now conducts various national security work and research in diverse areas, from renewable energy, nuclear fusion, space exploration, supercomputing, and efforts to mitigate global threats from disease to cyber-attacks. The lab is one of two U.S. sites preparing to produce plutonium cores for use in nuclear weapons.

With nearly 1,000 firefighters fighting the blaze, lab officials say critical infrastructure is well protected from the fire, which covers 175 square miles.

Still, scientists are ready.

“We’ve packed our bags, loaded cars, kids are home from school — it’s kind of a crazy day,” said Adam Atchley, a father of two and lab hydrologist who studies wildfire ecology.

Wildfires reaching Los Alamos National Laboratory increase the risk, however small, of chemical waste and radionuclides such as plutonium being discharged through the air or into the ash through runoff after a fire.

Mike McNaughton, an environmental health physicist at Los Alamos, acknowledges that chemical and radiological waste was blatantly mishandled in the lab’s early days.

“People had to win a war and weren’t careful,” McNaughton said. “The emissions are now very small compared to the historical emissions.”

Dave Fuehne, the lab’s team leader for measuring air emissions, says a network of about 25 air monitors surrounds the facility to ensure no dangerous pollution escapes undetected from the lab. When the fire broke out in April, extra large monitors were deployed.

Trees and undergrowth on campus are manually removed — 3,500 tons (3,175 metric tons) over the past four years, said Jim Jones, manager of the lab’s Wildland Fire Mitigation Project.

“We don’t burn,” Jones said. “It’s not worth the risk.”

Jay Coghlan, director of the environmental group Nuclear Watch New Mexico, wants a more thorough assessment of the lab’s current fire risks and questions whether plutonium pit production is appropriate.

This year’s spring fires also destroyed hilltop mansions in California and chewed through more than 1,100 square miles of tinder-dried northeast New Mexico. In Colorado, authorities said one person was killed Friday in a fire that destroyed eight mobile homes in Colorado Springs.

The sprawling fire in New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains is the largest blaze in the U.S., with at least 262 homes destroyed and thousands displaced.

Nearly 2,000 firefighters are now assigned to that blaze with a circumference of 501 miles (806 kilometers) — a distance that would stretch from San Diego to San Francisco.

Atchley says extreme weather changes the trajectory of many fires.

“A wildfire in the 70s, 80s, 90s, and even the 2000s will likely behave differently than a wildfire in 2020,” he said.

Atchley says he’s contributing to research to better understand and prevent the most destructive wildfires, overheated fires that leap through the upper crowns of mature pine trees. He says climate change is an undeniable factor.

“It expands the fire window for wildfires. … Wildfire season is year-round,” Atchley said. “And this isn’t just happening in the United States, but in Australia, Indonesia, and worldwide.”

He’s not alone in suggesting that the answer may be more common in lower-intensity fires deliberately set to mimic a cycle of combustion and regeneration that may have occurred every two to six years in New Mexico before the arrival of Europeans. Occurred.

“What we’re trying to do at Los Alamos is figure out how to safely implement prescribed fires…as it’s extremely difficult with climate change,” he said.

Examples of deliberately prescribed burns that escaped control include the 2000 Cerro Grande Fire that swept through residential areas of Los Alamos and across 12 square miles of the lab — more than a quarter of the campus. The fire destroyed more than 230 homes and 45 buildings in the lab. In 2011, a bigger and faster fire burned around the edges of the lab.

Atchley said the forests in the West could be seen and measured as a giant reserve that stores carbon and can help control climate change – if extreme fires can be contained.

Land managers say vast U.S. national forests cannot be thinned by hand and machine.

Linn, the physicist, says wildfire modeling software is being shared with land managers at the US Forest Service and the Geological Service a,nd Fithe sh and Wildlife Service for preliminary testing to see if prescribed fires are easier to predict and control.

“We’re not advocating that anyone blindly use any of these models,” he said. “We’re at that critical stage of building those relationships with land managers and helping them make it their model as well.”